The Creature Within

Dmitri Prigov, Portrait of Shakespeare, ballpoint and watercolour on paper

Over a cup of coffee and stimulating conversation, a friend introduced me to the work of the Russian poet, sculptor and artist, Dmitri Prigov (1940 Soviet Union - 2007, Russia).

Prigov started writing poetry as a teenager and penned 36,000 poems by 2005 in addition to creating graphic and performance works, designing sculptures for municipal parks, working as an architect, and co-founding the Russian Conceptualist movement (one of the most known members of which in the West is Ilya Kabakov) in the 1960s.

Dmitri Prigov, Portrait of Kandinsky, ballpoint and watercolour on paper

According to the cultural theorist Mikhail Epstein, Russian Conceptualism differs from Western Conceptualism in that the latter substitutes "one thing for another" whereas in Russia the object to be substituted is absent altogether.

Since non-conformist forms of expression were not well tolerated in the Soviet Union, in 1986 Prigov was arrested by the KGB and sent to a psychiatric institution from where he was eventually released after protests by notable cultural figures.

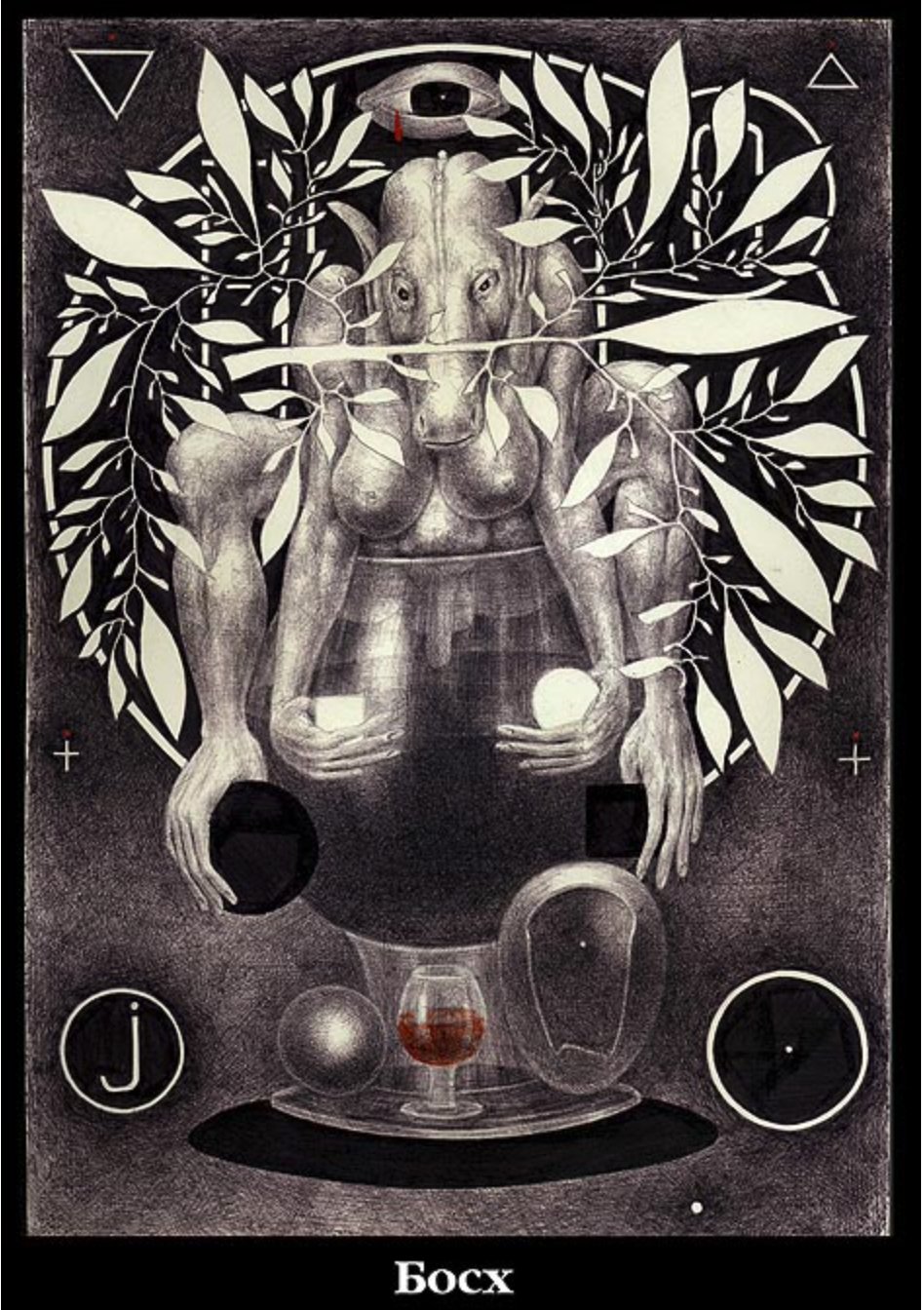

Dmitri Prigov, Portrait of Bosch, ballpoint and watercolour on paper

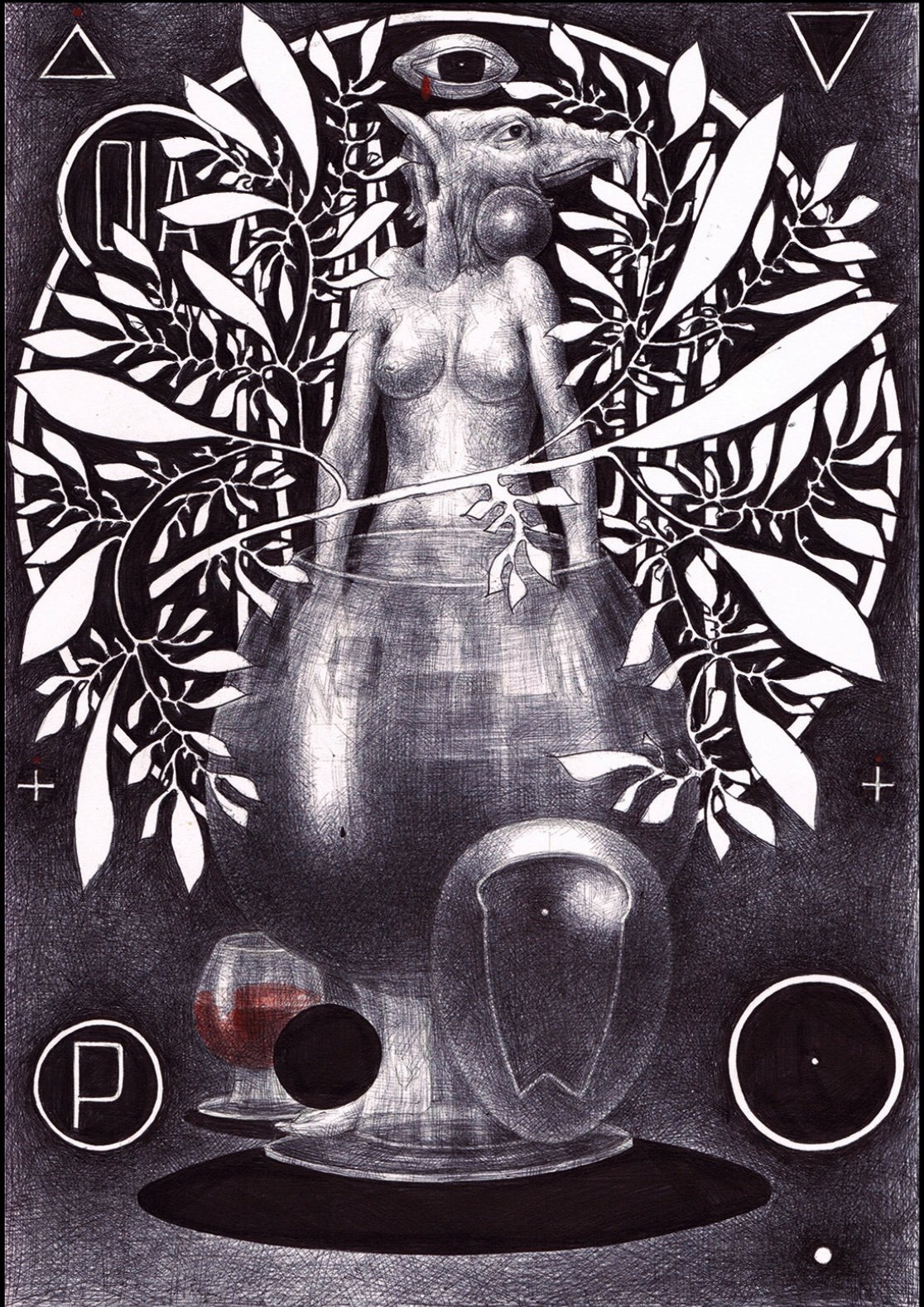

Beasts and monsters was a prevalent theme in Prigov’s art and writing. Not surprisingly, one of his most visually striking series of graphic works is The Bestiary.

Interestingly, the etymology of beast stems back to the Middle English beste - an animal but specifically “a marvellous creature or a monster” such as mermaids and werewolves. The etymology of monster on the other hand is likely traced to the Latin monstrum “a divine omen or sign”; monere "to remind, advise or warn”; and monstrare “to demonstrate”.

Dmitri Prigov, Portrait of Mondrian, ballpoint and watercolour on paper

It has been posited that Prigov’s monsters were created by his interest in the transformability and fluidity of the human experience. For example, in his 2002 “Vienna Stories” he writes: “A little boy, crossing the road, suddenly discovers in the middle of the street that he is not a small boy at all, but a huge creepy monster.” And more cryptically, in a 1998 quatrain from the Bestiary cycle:

“The monster is a beast that lives in the gap of all that is logical

Its tendency is to run away.

Man could borrow from it the principle of non-attachment.

It should be given an index of 117.”

Do with this as you will. Prigov has left the explanation (or the void in its place) to our imagination. The glass of wine in each portrait and the accompanying symbols? Your guess is as good as mine.

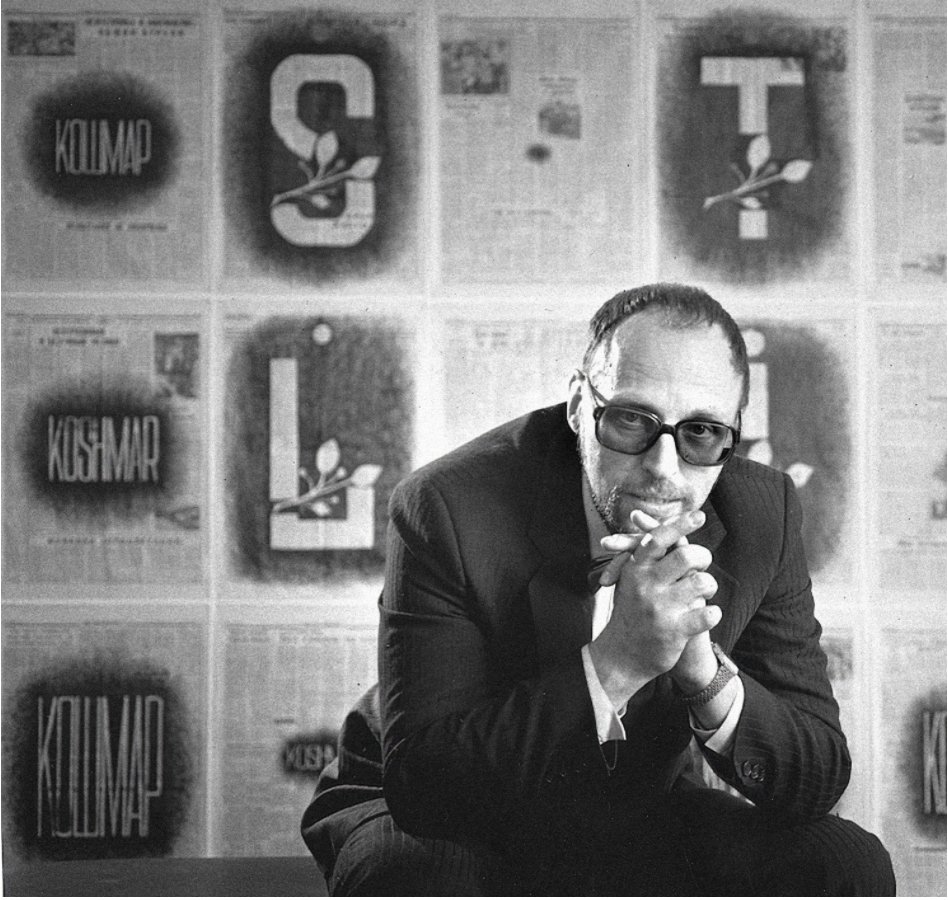

Dmitri Prigov

Dmitri Prigov’s works had been widely exhibited during his lifetime and are collected by the Tretyakov Gallery and Tate Modern, among others. Much more about his life and work can be found at the Prigov Fund. The website is in Russian but easily translatable into English - just click on Google’s translate function at the right of the URL bar: http://www.prigov.org/ru/gallery; and here is his Wiki page (in English): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dmitri_Prigov