Contemporary Chinese Landscape Painting: Same Same But Different

Chinese Landscape painting evolved into an independent genre in the late Tang Dynasty as an outlet for scholar-artists who sought in nature wisdom and an escape from their daily routine and official responsibilities.

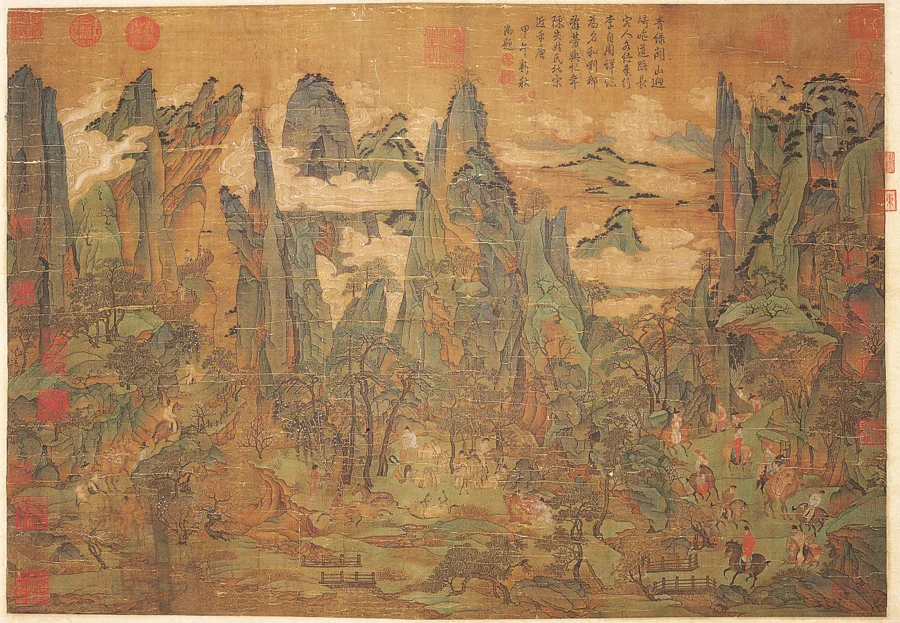

Li Zhaodao (early 8th century), Emperor Going to Shu, at www.comuseum.com

Centuries later and continents away, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote "How willingly we would escape … the sophistication and second thought [of cosmopolitan life], and suffer nature to intrance us,” concluding that “cities give not the human senses room enough” whereas nature “dwarfs every other circumstance". (Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essay VI Nature, from Essays: Second Series, 1844).

Waldo Emerson's words expressed both nature and himself. Similarly, the scholar-artists of China used calligraphic brushstrokes to express both their impression of nature and their inner selves. As words are to poetry, so calligraphic brushstrokes are to traditional Chinese landscape painting: the object is not to describe what is before the eyes but to convey the emotional impact of what is seen, imparting with it the soul of the artist through whose being the impact of the landscape is refracted and conveyed.

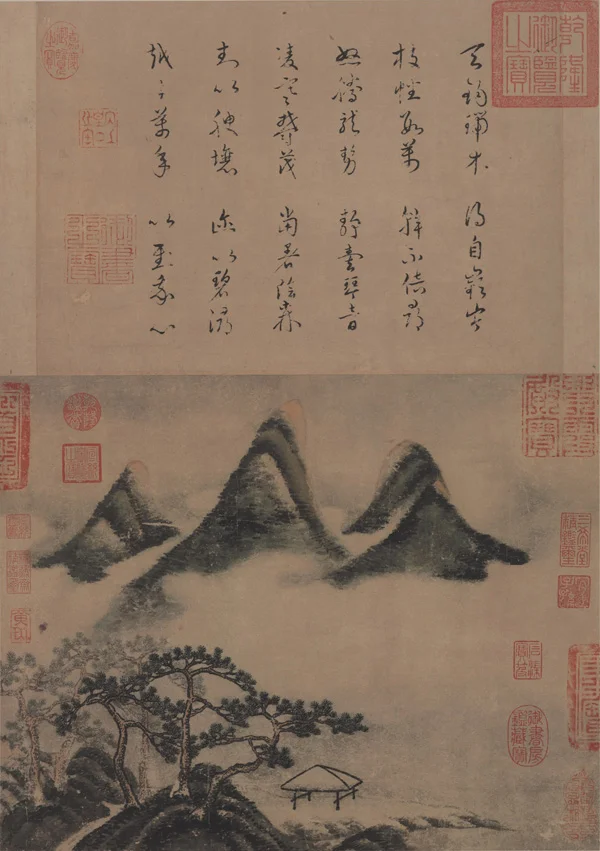

Mi Fu (1051-1107), Auspicious Pines in the Spring Mountains, www.comuseum.com

Using calligraphic brushstrokes as a means of self-expression became an important outlet for scholar-artists during the repressive Mongolian rule of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and continues to this day.

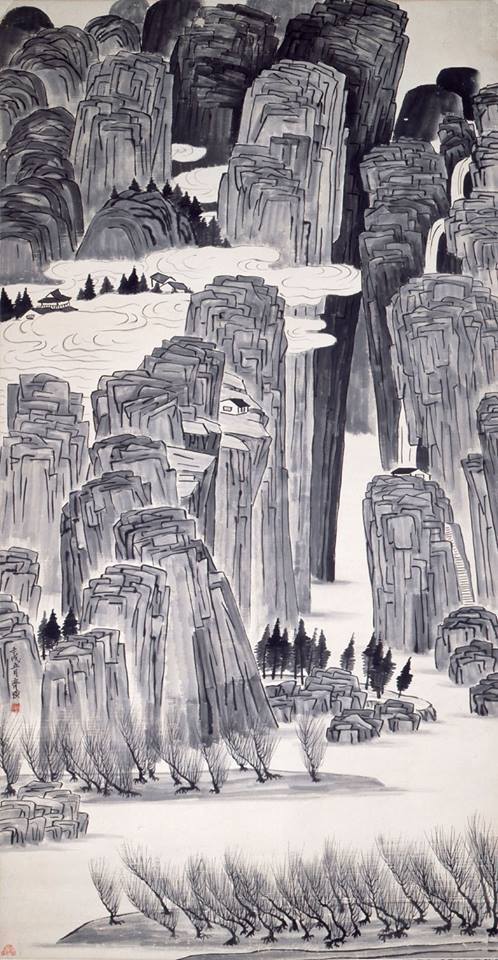

Qi Baishi (Chinese, 1864 – 1957), Song-style Landscape, Kyoto National Museum

Calligraphic brush strokes have transcended their original medium of ink painting and have given rise to the gestural painting of the Abstract Expressionists movement in America in the 1940s, influencing the likes of Willem de Kooning and Helen Frankenthaler.

De Kooning, Villa Borghese, 1960, oil on canvas, Guggenheim Museum

Helen Frankenthaler, Mountains and the Sea, 1962, charcoal, oil and canvas

Today, contemporary Chinese landscape painting is in turn influenced by the dynamic colour and movement explored by the Abstract Expressionists while at the same time remaining rooted in the expressive lyricism and philosophy of traditional calligraphic brushstrokes.

Chen Li (Chinese, b.1971), Evening Autumn Clouds, 2005-10, oil on linen canvas, U.K. Private Collection

Chen Li (Chinese, b.1971), Untitled, 2014, oil on linen canvas, 85cm x 85cm

The result is an exciting synthesis of East and West and a vast field for continued exploration of self-expression through art.